Last year, a South African government-backed fund invited applications from would-be junior miners, hoping to find that the country’s mineral exploration business was not ex-growth, as is sometimes suggested. The response was overwhelmingly positive. Billions of rands’ worth of projects flooded the inbox of the R400m Junior Mining Exploration Fund (JMEF), as the initiative is called.

About R120m has been allocated to six projects so far. For the successful candidates, the money — about R20m apiece if divided equally — is probably enough to extract initial drill results, reckons former Harmony Gold CEO Bernard Swanepoel.

The trouble is that while it’s a good start, it doesn’t take the projects further. But in May, Jacob Mbele, director-general of the department of mineral & petroleum resources (DMPR), told the Junior Indaba conference, chaired by Swanepoel, that “there just isn’t enough money”.

Getting a mining project off the ground requires time and piles of money — the kind of endeavour that only private capital can fund. New copper mines currently under development in South America have been in gestation for over 20 years. The average capital intensity of seven copper projects studied by Goldman Sachs increased 50% from pre-feasibility to production.

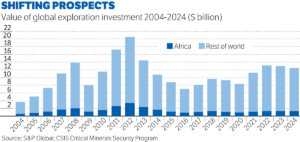

Investors, however, are firmly hands-off South Africa. Where once it commanded 35% of Africa’s exploration budget, it now only attracts 7%. In 2007 South Africa still contributed 22% of African exploration spend, worth $403m; that had fallen to $121m by 2024.

Efforts by mineral & petroleum resources minister Gwede Mantashe to have South Africa recapture 5% of global exploration expenditure, which it last achieved in 2003, have failed miserably. South Africa controls less than 1% of global exploration capital.

“Countries with fewer resources but better governance — like Namibia, Botswana, Ivory Coast and even Malawi — are attracting investment,” said Paul Miller, a former resources banker. “The mining sector is in decline. Investor flight, regulatory chaos and policy failures are driving capital elsewhere, leaving the country’s mining future at risk.”

Miller’s view, that the government has for decades made it difficult for investors to place money in the country, is resoundingly shared by attorneys, investors and company executives. Some of them, speaking at the Junior Indaba, were shocked by an amendment bill to the 2002 Mineral & Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), gazetted on May 21.

While the bill is not all bad — it makes provision for greater policing of illegal mining and clears up confusion over the ownership of mineral by-products — it paves the way for another round of empowerment, which the industry claims is not needed. Until it was corrected on June 10, the bill also planned to impose empowerment obligations on mineral exploration companies that normally rely on equity to finance deals.

In addition, the government’s attention seems to have been inordinately fixed on illegal mining, a long-standing problem but one that became big news only in January when 78 people died at a closed shaft at Stilfontein in North West.

Importantly, the bill makes a big deal of encouraging artisanal mining, which is probably the least financeable of all mining and exploration endeavours, instead of pumping finance into the country’s mainstay junior sector. This muddies the water for exploration firms.

“What was interesting for me from reading the bill was there seems to be quite a big gap in what is applicable to assist the junior space,” said Lili Nupen, a director at law firm NSDV.

“So while we talk about the artisanal and small-scale miners, what about the junior space? There is the opportunity to take our legislation as it is and create more flexibility for the junior mining space, encourage more investment, promote exploration, and do it through things such as exemptions and tax holidays.”

Nupen also questions how the bill intends to manage artisanal mining via an unclear process of invitation, subject to ministerial discretion, and only to black persons on terms set down in the Broad-based Black Economic Empowerment Act.

Countries with fewer resources but better governance — like Namibia, Botswana, Ivory Coast and even Malawi — are attracting investment. The mining sector is in decline. Investor flight, regulatory chaos and policy failures are driving capital elsewhere, leaving the country’s mining future at risk – Paul Miller

There are a host of other concerns with the bill, which is out for public comment until August 13. Top of these is making a separate piece of legislation — the Codes of Good Governance — enforceable law in the act. Hulme Scholes, a director at Malan Scholes Attorneys, said: “A likely outcome is that new BEE regulations will follow the bill’s implementation.”

This could give the minister an opportunity to set new empowerment targets for mining companies, circumventing a high court judgment in 2021. In that ruling, the court found in favour of the Minerals Council South Africa, which had argued that mining companies could not be asked to re-empower once they had complied with the Mining Charter — a companion document. In essence, the court found the Mining Charter was policy, not enforceable law.

The upshot is that the bill is likely to put another damper on junior mining investment in South Africa. “It doesn’t provide an incentive for anyone to risk their capital at that early stage of mining investment,” says Minerals Council CEO Mzila Mthenjane. “We will get investors sitting on the sidelines.”

Don’t tell that to Mosa Mabuza, CEO of the Council for Geoscience (CGS), a unit of the DMPR that set up the JMEF with the Industrial Development Corp. “I don’t know why we keep moaning about legislation,” he told the Junior Indaba. “I don’t know why we just talk about imperfect legislation and how it’s crippling. I think we must just get going. Do we believe in exploration? Yes. Do we believe there are minerals? Absolutely. Can we get them going? I think absolutely, certainly so.”

Mabuza is a well-liked figure in the mining sector, partly for his can-do attitude. Where other government departments make an art out of procrastination, the CGS is proactive. “The quality of geology in this country is grossly inconsistent with the level of exploration,” he told the Indaba.

He’s right. South Africa’s provinces are underexplored, especially using new exploration technology. His enthusiasm is typical of how start-up miners like to operate, immoderately optimistic. This speaks to a history of endeavour the country’s miners like to wear as a badge.

Yet South African mining is in decline, according to Errol Smart, the former CEO of Orion Minerals, one of the country’s few JSE-listed mineral developers. “We were the mining hub of Africa; we were the heart of it, and it’s busy failing,” he said.

Terminal decline?

Where once South Africa boasted the swankiest mining houses, it now exports its executive skills. The world’s second-largest gold firm, Barrick Mining, is led by South African geologist Mark Bristow. The president of the largest, Newmont, is Natascha Viljoen, formerly CEO of Anglo American Platinum (now Valterra Platinum). Two of the largest diversified miners — Glencore and Anglo American — are led by South Africans, schooled in the country but sitting at desks in Switzerland and London.

Mining’s rich history in South Africa is reflected in its sophisticated legal practice and its banks, which continue to fund some of Africa’s largest mining deals. In June FirstRand’s Rand Merchant Bank was one of two parties in the $470m debt and equity refinancing of Ghana’s Asante Gold.

Yet while the mining industry is not as dominant as it once was, it’s still a critical component of the economy. It accounted for 6.1% of GDP (with primary sales totalling R800.9bn) last year and employed 474,876 people, generating R191bn in employee earnings. Every job in mining results in the creation of 10 other jobs, according to Minerals Council data. This means nearly 8% of the population relies on mining.

As importantly, the sector still has an opportunity to play on the global stage. South Africa contains the world’s largest resource of manganese, important for steel and batteries, and the most platinum group metals. It’s also China’s largest supplier of chrome, while its gold mine resources, though deep, compare to the world’s best. Coal is abundant.