South Africa’s main mining unions have expressed concerns about the sector’s reboot in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. The crisis has also seen labour, industry and government find common ground, which could herald a new era of cooperation after decades of mistrust and conflict.

Relations between the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) and industry have never looked rosier, despite outstanding issues around the Mining Charter.

DMRE minister, Gwede Mantashe, a former miner and unionist who is a political heavyweight in the governing ANC, was a driving force behind efforts to allow the industry to reboot to 50% capacity in May when the hard lockdown was eased from ‘phase 5’ to ‘phase 4’. This came after coal mines providing Eskom, as well as some mechanised and open-pit operations in the iron ore and platinum group metal (PGM) sectors, had been allowed to operate in April.

People familiar with the matter say that the moves were met with resistance by some in the cabinet and the National Command Council, which is charged with overseeing the state’s response to the pandemic, and Mantashe had intense discussions with unions and industry over the matter.

The motive to keep some mines running and then to have a gradual restart were clear: the economy was cratering and South Africa was also losing vital foreign exchange. In 2019, mineral export sales amounted to almost R350bn and the sector accounted for 8.1% of GDP, according to Minerals Council data, as well as employing about 450,000 people. Keeping people at work at a time when unemployment, poverty and hunger were surging was a key concern of Mantashe’s.

This article was first published in the Mining Yearbook 2020 which is available here: https://www.miningmx.com/the-mining-yearbook-2020/

The main mining unions, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) and the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), expressed strong opposition to the reboot. Yet, revealingly, it has triggered – as of late June – none of the unrest that has periodically rocked the sector in recent years.

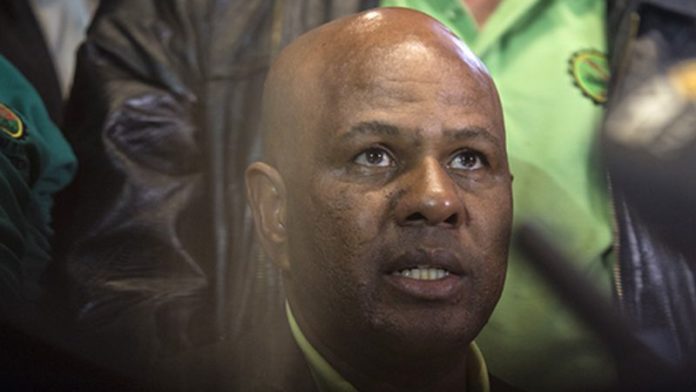

Indeed, AMCU, headed by Joseph Mathunjwa – who sees the world through a prism of intense class conflict, African nationalism and evangelical Christianity – headed to court over the issue to demand that the DMRE gazette minimum COVID-19 guidelines.

AMCU was smarting after a disastrous five-month strike in Sibanye-Stillwater’s gold unit that achieved nothing, and managed only moderate wage increases after months of talks with the newly-flush platinum sector. But Mathunjwa knew where to pick his fights and heading to court, with top human rights lawyer Richard Spoor leading the charge, was a sensible move.

In reality, the Minerals Council of SA and AMCU were not far apart on the issue. Many of AMCU’s demands for measures to contain the spread of COVID-19 in the mines were already being followed as operating procedures that the Minerals Council’s members were taking. The court ruled in AMCU’s favour, but the industry was largely on board. And its intensive screening and testing measures have helped to give an indication of the pandemic’s extent in mining communities.

The pandemic’s timing has also helped to ease potential tensions.

If it had struck a few years ago, the platinum sector for one may well have been crippled. It was burning cash at an alarming rate in the face of social and labour ructions, depressed prices and steadily rising costs, notably for power and labour. It certainly would not have been in a position to pay employees for staying at home.

Not all companies have done so, admittedly, but several have been in the position to do so because of the spike in prices and other initiatives, including a pivot to mechanisation where South Africa’s arduous geology allows. Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) to the end of May paid out an astonishing R1bn to employees who did not work because of the lockdown.

This needs to be put in some context. Amplats’ profits more than doubled in 2019, leaving its balance sheet with net cash of R17.3bn compared to R2.9bn at the end of 2018. Its total dividend for the year was a whopping R14.2bn. So the R1bn paid out to the end of May to employees who sat at home was 7% of what was paid to shareholders for 2019, and is an even smaller percentage of its net cash position.

But one of the remarkable things about 2020, at least at the midway point of this tumultuous year, has been the absence of labour unrest

This state of affairs highlights two crucial things: first, that the company could afford to keep paying wages in the absence of productivity and, to its credit, did so. Secondly, it means that in cases such as this, the private sector is assuming the role of the state by providing a social safety net – again, because it can afford to in some cases. This stands in stark contrast to the increasingly indebted government.

Initiatives such as this are surely laying the foundation for improved labour relations in the mining industry. Companies that have not been as generous because of balance sheet or other issues may have a bumpier post-COVID ride. But one of the remarkable things about 2020, at least at the midway point of this tumultuous year, has been the absence of labour unrest. And this is despite understandable worker fears about the pandemic, heightened prospects for wider social unrest and vocal union opposition to the sector’s reboot.

Such combustible material would typically fuel the flames in South Africa’s fraught social environment. That it has not done so yet bodes cautiously well for the future.