COMMENTING on a decision by the Tanzanian government to blockade gold-bearing concentrate produced from Acacia Mining’s Bulyanhulu and Buzwagi mines earlier this year, Investec Securities was moved to articulate the fear the East African country had become “an irrational state”.

This is how foreign investors view the wave of populism running through Africa with similarly sweeping changes to mining codes or resources-related legislation being contemplated in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and, of course, in South Africa.

“The tentative recovery in global demand for some metals has induced fresh courage in cash-strapped countries, like DRC, or interventionist governments, like Tanzania’s, to seek greater control over the revenues from extractive sectors,” said Robert Besseling, executive director of consultancy, ExxAfrica.

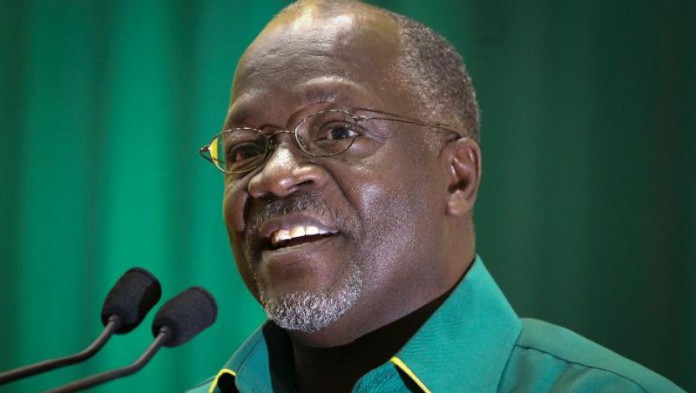

“Moreover, miner-bashing remains politically expedient,” he added referencing John Magufuli, the Tanzanian president. Known as ‘The Bulldozer’, owing to his previous reputation for wanting to improve the country’s road infrastructure but now more descriptive of his hostile treatment of mining companies, Magufuli has scandalised Acacia Mining and a host of other mining firms after introducing legislation that up-ends the previous regulatory dispensation.

Three pieces of legislation, ratified in Tanzania’s parliament in short order during July, provides the government with the right to take a free-carried 16% stake in mining companies in compensation for previously unpaid taxes, and the option of buying up to a 50% threshold. Royalties on revenue have also been jacked up to 6% from 4% previously, while a 1% clearing fee on exports has also been imposed.

The ban on Acacia’s concentrate exports is premised on two presidential reports that claim the company has under-declared the value of the concentrate over a period of years, which is tantamount to tens of billions of dollars in unpaid taxes – a claim the company has dismissed as an economic impossibility.

If Acacia had been under-declaring the value of its concentrate exports as the Tanzanian government claims, it would mean “…they are the two largest gold producers in the world, that Acacia is the world’s third-largest gold producer, and that Acacia produces more gold from just three mines than companies like AngloGold Ashanti produces from 19 mines”, the company’s CEO, Brad Gordon, said in a statement in June.

Miner-bashing remains politically expedient – Robert Besseling

According to Louis Coetzee, CEO of Kibo Mining, a coal development company that has been operating in Tanzania for years, said the current problems in Tanzania were an attempt to install conformity, but against a backdrop of confused and poor law-making in the past in respect to mining companies operating in the country’s borders.

Said Coetzee of the new legislation in Tanzania: “Regulations were created for the exploration industry that took no account of what would happen when the exploration companies became producing companies. We warned them, but they didn’t listen.”

Coetzee who has been active in Tanzania for more than 10 years, added: “Then you got a situation where producing firms were benefitting from laws only exploration firms should enjoy. They have amended the mining code, mainly in 2010, but Magufuli is just trying to impose the laws as they should have been imposed.”

He said that although this approach had come from a good place, the implementation has been wrong. He cited an example where Magufuli banned the import of coal to the country in order to support its domestic development. “The objective was why are we stifling our industry. We are a country with vast coal resources; why is it not developing?

“But then you get this draconian intervention where we can’t import any coal. I don’t think that was correct in my personal opinion. It is just my view, but the objective was to actually encourage and grow the local industry; to get people to focus rather than just import it from somewhere else,” he said.

Acacia, meanwhile, is also struggling to claim back VAT payments to the Tanzanian government, a problem that is shared with other mining companies in other jurisdictions. In October 2016, Randgold Resources faced down the Mali government, which threatened to permanently shut its corporate offices on the basis it was owed $80m in unpaid taxes.

The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes had recently awarded $29.2m plus costs to Randgold’s Loulo for taxes found by a tribunal to have been wrongfully collected by the Malian government. In the end, Randgold Resources CEO, Mark Bristow, agreed to a dispute mechanism and advanced $25m on the proviso that if the government claims were unfounded, the monies would be returned.

First Quantum Minerals is also fighting a “vexatious and untrue” claim by Zambia’s state-owned copper company ZCCM Investments Holdings that is local subsidiary, Kansanshi Mining had been involved in fraudulent activity with the parent company.

Meanwhile, Bristow was in action again regarding planned mining code changes by the DRC to a shelved 2015 draft which included a stability clause for a new project that would drop from 10 years to five years, mining royalties that would increase to 3.5% from 2.5%, corporate tax increases to 35% from 30% and state participation, which would increase to 10% from 5% currently. There were also planned steep increases in customs duties on fuel and intermediate goods.

Making the point that the Kibali gold mine, which equally between Randgold and AngloGold Ashanti, had contributed $2.2bn to the Congolese economy in taxes, salaries and payments to local suppliers, Bristow said: “I am concerned that the government is not engaging in open and inclusive consultations with the industry and appears to be proceeding from a pre-determined position that may put existing and future mining investments at risk.

“The mining industry is the main engine of the Congolese economy. Government and the private sector must work together to find the best way of growing this industry and to avoid potentially damaging short-term actions by realistically considering their consequences,” he added.

More recently, the DRC’s Central Bank announced stiff new financial penalties for companies that fail to repatriate at least 40% of their revenues from mineral exports. The decree imposes a penalty of 1% of the non-repatriated sum for each day that is is not repatriated. It also decrees a fine of up to 200m Congolese francs – about $125,000 – for failure to communicate to the central bank details of a foreign bank account.

Said Goldman Sachs in a recent report: “While Randgold and AngloGold have complied with the decree, we highlight that this comes after the government is looking to revamp the mining code. This could represent increased uncertainty for miners in the region.”

Mxolisi Mgojo, CEO of Exxaro Resources, said political and regulatory uncertainty in Africa was echoed or was an echo of global failure to address the needs of the populace. “There’s nothing unique about Africa than what you are experiencing anywhere in the world where systems that are supposed to be serving the people begin to be self-serving. Then they are not dealing with the issues of the people. And the people will respond, either through violence or through the ballot box, or whatever,” he said.