Many in the world are talking of “the great reset”, which it is hoped will see the emergence of a fairer world, a greener world and a world more deeply concerned about the human impact on the planet. On the other hand, the countervailing forces are possibly stronger: more inward-focused economies, a trend towards protectionism, a weakening of globalisation and a strengthening of the currents of nationalism, which had emerged prior to the global stop brought by the pandemic.

In South Africa, the need to push the reset button is more urgent than elsewhere. The country entered the COVID-19 crisis already in recession, with a growth forecast for 2020 of 0,4% by the SA Reserve Bank and 0,9% by National Treasury. Over the past five years the economy has been stagnant, GDP per capita has been in decline and unemployment – which hit 29,1% in the fourth quarter of 2019 – has been on the rise, climbing to 30,1% in the first quarter of this year.

This article was first published in the Mining Yearbook 2020 which is available here: https://www.miningmx.com/the-mining-yearbook-2020/

Electricity supply constraints have cast a long shadow over the economy’s growth potential. Public finances have been under pressure to an extent unprecedented during the democratic era – with the February budget projecting that the debt-to-GDP ratio would reach 71,6% over the next three years – on a trajectory that showed no sign of stabilising.

The COVID-19 crisis has blown all of these metrics further out, with the SA Reserve Bank now projecting negative GDP growth of 7% for 2020 and rating agency Standard and Poor’s expecting that the debt-to-GDP ratio will reach 85% by 2023.

The difficulty in resetting the economy for South Africa is that the country has strong stakeholders, but whose interests are not well-aligned. It is no exaggeration to say that it is politics that has hampered South Africa’s ability to reach its potential, rather than economic policy, for at least the last decade. While there is a broad consensus that the levels of inequality – South Africa is by far the most unequal country in the world – are not sustainable, there is little consensus over what to do.

BACKLASH

While economic orthodoxy still holds sway in government and in ANC economic policy circles, it is not without contestation. Among the left – which includes some in the ANC, the SACP and labour federation Cosatu – there is a backlash against treasury policies, such as fiscal consolidation and measures to contain spending. South Africa’s sluggish growth rate is taken by these groups to be a consequence of economic orthodoxy that has failed and, while not an immediate threat, the ANC is increasingly vulnerable to the pull of populist ideas, dressed up in the rhetoric of economic transformation.

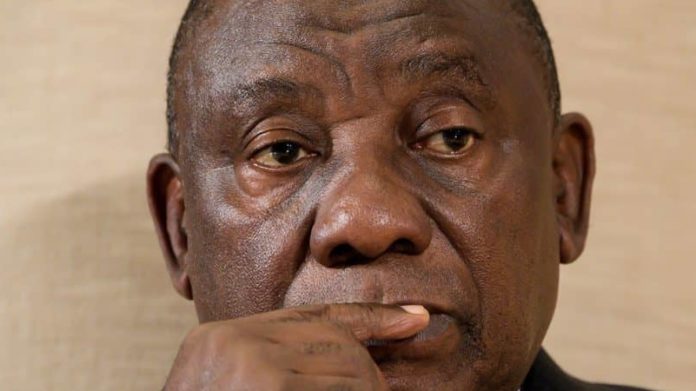

Further complicating this picture is that the ruling party itself is not united. The government at a leadership level – that is the cabinet – is not sufficiently focused, skilled or united to drive through a coherent programme. President Cyril Ramaphosa has wanted to lead from behind. Since becoming president in 2018 he has not pushed a firm reform agenda; his preference has been to tread softly on political ground and readily compromise when challenged, particularly by organised labour.

The difficulty in resetting the economy for South Africa is that the country has strong stakeholders, but whose interests are not well-aligned

How the reset happens, which policy elements are emphasised and which reforms are possible will be a product of how these dynamics play out. That said, the state is weak, excessively bureaucratised and lacks the capacity to implement programmes – even where agreement is reached.

REFORM, REFORM, REFORM

A raft of reforms is on the table. Last August finance minister Tito Mboweni published a growth strategy document, which in broad terms was adopted by the cabinet and the ANC. The reforms are pretty much the same structural economic reform measures that have been promised for successive years by successive finance ministers. Essentially, the idea is reduce the costs of doing business, modernise network industries, lower barriers to industry and promote export competitiveness.

Most notable for the mining and industrial sectors are network industries – such as energy, logistics (ports and rail) and broadband – all major constraints on growth. Mboweni’s reform agenda emphasises introducing competition and private participation, restructuring markets and lowering costs.

But progress has been painfully slow. Energy, which is the biggest binding economic constraint and top of mind for mining companies as costs continue to rise, remains weighed down by Eskom, where deep operational and financial problems endure.

Eskom restructuring – which is key to liberalising the energy market, increasing security of supply and relieving the stress on the fiscus – was identified as a top priority by Ramaphosa in his State of the Nation speech in February 2019. The decision to disaggregate the company into three – generation, transmission and distribution – came on the back of recommendations by Ramaphosa’s own expert task team. But almost 18 months on, little has happened. While Eskom is in safer hands with new CEO André de Ruyter at the helm, the unbundling has stalled and been shifted out by at least two years. A major milestone – the legal establishment of an independent grid owner and operator – is now only expected to take shape in 2022, with no firm date on final legal separation.

In the wider energy sector some regulatory reform has happened, although the impact for the mining industry could be less than initially thought. Energy policy in South Africa has been politically fraught with strong opposition from the left to independent power producers (IPPs), which is seen as amounting to “privatisation” of electricity. There is also still a vociferous nuclear lobby, even though the grand plan for a massive Russian nuclear build has been blocked.

Energy policy in South Africa has been politically fraught with strong opposition from the left to independent power producers which is seen as amounting to privatisation of electricity.

Mineral resources and energy minister Gwede Mantashe has been cautiously picking his way through these dynamics. Given the urgency of the electricity supply constraint, due to political factors, Mantashe has moved very slowly to initiate new procurement from IPPs. This is finally on track, with a bidding process about to commence. It will, however, be several years before new plants come online as bidding, adjudication and financing must all be concluded before construction can begin.

YES, MINISTER?

For the mining sector, self-generation of electricity, which has also been opened up for licensing by Mantashe, shows some promise. However, because a large number of uncertainties remain in the regulatory environment, self-generation is still a costly and risky endeavour for most mining enterprises. It is still unclear, for instance, whether the National Energy Regulator of SA (Nersa) will approve mining self-generation projects as a matter of course, as these have not been explicitly provided for by ministerial determination.

In addition to this, projects that will connect to the Eskom grid must be licensed, for which the requirements – such as environmental approval and rezoning of land – are costly to undertake without certainty that the licence will be granted. Wheeling costs for the use of the grid are unknown and it is also uncertain whether generation projects built to supply mines will be able to sell electricity to other customers, beyond the life of the mine.

But although he has opened the door to more private sector participation, Mantashe has also made clear that he intends to keep his hand on the regulatory throttle. In a major policy change, he has cleared the way for municipalities to generate or purchase electricity from other sources. However, ministerial approval must first be obtained. Self-generation of over 1MW also requires application for a licence via the minister’s office.

During his time as minister – which is only a little over a year in the case of the energy part of his portfolio – the changes to regulation demonstrate that Mantashe has an appreciation of the constraints facing the private sector. His support for the re-opening of mines during the COVID-19 epidemic was especially notable, coming at a time when fear of the epidemic was high and mining and living conditions made working safety difficult. While other cabinet colleagues showed excessive prudence, Mantashe was decisive that, because the mining sector faces a challenge for survival, a longer shut down would mean enormous job losses.

While Ramaphosa has always been publicly supportive of Mboweni, he is also constantly mindful of the wider ANC dynamics. This makes policy reform slow and ponderous and, while for the most part it does eventually happen, the impact that an overall programme would have risks being lost.

In April, the first full month of the lockdown, Stats SA recorded that mining production plummeted by 47%. Production though was already in decline due to shutdown’s elsewhere in the world, and fell 18% in March. By June, mining was still operating at around 50% of capacity.

While Mantashe has shown a greater affinity and insight into the mining industry than many of his predecessors, there are firm limits to the extent to which he is prepared to accommodate private sector and investor interests. The clearest evidence of this is his commitment to transformation of the industry, especially of ownership.

The failure of the industry and government to reach agreement on the “once empowered, always empowered” aspect of the Mining Charter continues to overhang future investment. While encouraging noises were recently made from both sides that a court battle was best avoided, it is difficult to see where compromise might be possible. The ANC as a whole is firmly committed to black economic empowerment, notwithstanding some of the negative effects of the policy on investment and the cost of government procurement.

Mantashe’s political stance – which besides transformation also encompasses a suspicion of the market and a firm belief that the state should be a major participant in the economy – is reflective of the dominant politics within the ANC. While many in business had expected that Ramaphosa would counter these tendencies, he has turned out to be much more of a party man than anticipated.

While Ramaphosa has always been publicly supportive of Mboweni, he is also constantly mindful of the wider ANC dynamics. This makes policy reform slow and ponderous and, while for the most part it does eventually happen, the impact that an overall programme would have risks being lost.

As South Africa emerges from the lockdown, with the curve of the epidemic still ascending, ambitions for a reset are high. But even though the COVID-19 crisis should galvanise stakeholders into joint action, politics may well get in the way again.