MICK Davis has had a singular career. Firstly, there’s the knighthood, awarded in 2015 for his efforts in Holocaust commemoration and education. Then there’s the three-year stint as treasurer and then CEO of the UK’s Conservative Party, under the leadership of then prime minister, Theresa May.

But for the most part it is as a mining tycoon – ‘Mick the Miner’ – as the City once dubbed him – that Davis is renowned. The last three years have been among his quietest following the 2017 closure of X2 Resources, the $6bn privately backed fund. This year, however, marks his return as chairman of Vision Blue Resources (VBR), a company initially backed by $60m in private funds.

Davis says VBR is not like his other mining ventures.

“I’m not building a mining company; I’m essentially investing in opportunities where I think value can be created. I’m adding combinations of my financial capital and my human capital to ensure these projects and opportunities can track up the value curve. That’s why Vision Blue is different to the rest, and that’s essentially what we’re trying to look at.”

‘The rest’ refers to Davis’s previous roles, firstly as the CFO of Billiton, the South African company that merged with BHP to create the world’s largest mining company, and then subsequent roles as founding CEO of Xstrata, and X2 Resources.

The way Davis sees it, Billiton represented the emergence of a newly democratised South Africa on the international mining stage, while Xstrata was driven by the surge in demand for commodities as a result of growing urbanisation in China. X2 Resources, which Davis started after Xstrata’s merger with Glencore, also sought to capitalise on China’s commodities boom, recognising in a debt-burdened mining sector the chance to buy projects cheaply.

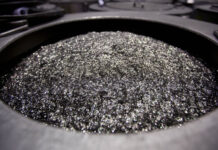

VBR is a different animal, says Davis. Its initial investment – in a graphite project in Madagascar through a $29.5m stake in NextSource Materials – is aimed at supplying the electric vehicle market, which Davis believes is part of a new, potentially multi-generational phase in elevated commodities demand. What appears unique about decarbonisation is it has widespread, almost global, political sanction.

“Here we’re seeing the key driver being the transition to green energy and the almost globally mandated reduction of CO2, and that is leading to a new secular shift in demand,” he says. According to Davis, this is not a secular shift created by a country industrialising like China, or massive growth in GDP, but as a result of “… mandated political structural change in the way that economies function”.

Davis thinks demand for minerals such as graphite, which is processed for use in the lithium-ion batteries needed to power electric vehicles, will be profound, easily outpacing in duration and impact the China-led super-cycle of 2002 to 2019.

The investment in the Madagascar mine has been followed by a $300m capital-raising after VBR teamed up with the New York-listed SPAC ESM Acquisition Company. The SPAC’s mandate is to hunt for green energy investments. Separately, VBR has invested $12.6m in Ferro-Alloy Resources Group with a view to expanding a vanadium project in Kazakhstan. Previously a steel-strengthening agent, vanadium is now being used in new ways, including for large-scale power storage.

VBR’s quick-fire investments compare favourably with the stationary nature of X2 Resources, where Davis’s financial backers declined to sign off on at least three deals. He describes this situation as a governance issue but says, had the approval been given, X2 Resources would have returned “ten times the money invested in something like 70% off internal rate of return”.

X2 Resources represented a lean period for Davis. Between it and VBR he helped found Niron Metals, which had an option over West African iron ore but remains heavily hamstrung by a combination of politics, logistics and investment cost. He is keeping Niron Metals on the backburner, especially given the centrality of iron ore in global decarbonisation efforts.

Major miners hamstrung

One transaction that X2 Resources sought to close was the purchase of Rio Tinto’s Australian thermal coal assets.

At the time, it was a pretty big deal in terms of strategic shift, whereas today the major diversified mining companies are falling over themselves to sell or close their emission-heavy assets, especially as investors take a critical view of their environmental, social and governance standards. As a result, the large-cap, diversified mining sector is constrained in its ability to move with speed on opportunities. Diversified miners also can’t easily justify investing in early-stage projects given the low impact they would have on earnings and dividends, and the high-intensity management. For entities such as VBR, this spells opportunity.

“They’re going to have to devote a huge amount of management time without much effort and they get no credits in their multiple,” says Davis of large mining groups. “Whereas I come along and I put some money into NextSource Materials, whose share price goes up threefold by virtue of me being there, and credentialising the project – and that’s tremendously valuable for my investors.”

Since VBR is not a mining company, there’s already a strategy to exit the investments. According to Davis, this will be just as the projects move into production. At some point, mining companies will have to switch from dividend payments to investing in replacement reserves and growth in minerals production. That’s when VBR will be ready to provide those growth options.

China risk

Davis thinks it’s also critical for the West to start building in both upstream and downstream productive capacity in the decarbonising of minerals.

It’s a mistake to have allowed China a march on green energy technology. “It gives them disproportionate commercial and strategic power. I do think that the West needs to catch up and basically our view is that the greater part of the value-add chain is down to the process as opposed to simply in the mining chain.”

To this end, VBR is weighing up potential locations for a battery materials factory that will produce a purified form of graphite for use by end-users such as Tesla, the US carmaker. One potential location identified by VBR is South Africa, potentially even Gqeberha, formerly Port Elizabeth, where Davis was born. However, he questions South Africa’s ability to attract investment.

“The ideology and politics are inimical to investment. You have a situation where it [the government] is driving an ideological agenda which doesn’t make it easy to invest, and increases cost of investment.” That affects everything, says Davis, including logistics, which would be South Africa’s ace card considering its proximity to Madagascar.

“I’m not going to say that I would never invest in South Africa. I’m just saying that it’s easier to invest in other countries.”

For the full story as it appeared in our 2021 Mining Yearbook, please visit the special ebook section below.