SINCE his appointment as CEO in 2021, Glencore boss Gary Nagle has nailed his colours to a mast of culture improvement and mergers & acquisitions. But a third strategic initiative, recycling, was in evidence during a site visit to the firm’s Canadian assets in September. What is now a modest initiative is set to become a key part of the business.

Modest in some respects, but meaningful in others: Glencore recycled 30,500 tons of copper, 1.3-million ounces of silver and 1,500 tons of cobalt last year, equivalent to the output of a small base metals company.

What could be possible if Glencore were to throttle up? Quite a lot, it seems. Glencore plans to earn about $1bn from recycling by 2030, against $250m last year — less than 1% of group earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (ebitda).

The group has some competitive advantages.

One is that recycling plays to its DNA as a metals merchant. Nagle’s predecessor, Ivan Glasenberg, once remarked that his career at Glencore was sparked after marvelling at how money was made by moving candle wax from South America to Japan. In nearly 30 years at the group, 19 of them as CEO, Glasenberg presided over impressive growth in trading. Few rival companies can compete, though they try. In 2022, a fifth of Glencore’s $34bn in ebitda was from commodities marketing.

It hasn’t been without controversy. In Nagle’s first year, Glencore owned up to corruption in its trading, paying $700m in penalties. The charges were damaging and continue to affect the group. An independent compliance monitor continues to stalk Glencore’s corridors as part of the settlement with the US department of justice.

But there’s no doubting the latent potential in the group’s network, says banking group Citi. “Sourcing feed from thousands of suppliers and selling processed material to all possible types of customers is something the other miners would find hard to replicate,” it said.

To feed the marketing machine, Glencore has an even larger network of industrial assets: mines and processing facilities stretching from its 94-year-old Portovesme facilities in Sardinia to Penang, to Mumbai and to San José in California. In terms of Glencore’s plans, some of the hydrometallurgical and pyrometallurgical processing facilities in this footprint can be repurposed for relatively modest capital outlay to boost recycling production.

That’s music to the ears of investors who are wary of mining companies overspending on growth instead of paying dividends. Citi said that in its view, Glencore’s global network of smelters gives it a unique advantage in terms of capital intensity and in speed to market.

Upgrade needed

Recycling, or secondary supply as it’s sometimes called, is not new to mining but it hasn’t been embraced in quite the way Glencore intends. That’s because current supplies are poor.

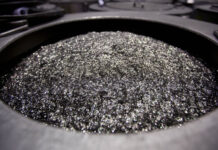

Annually, an estimated 50Mt of ‘e-waste’ or scrap electronics, also called “black mass”, is generated. Only 20% of this is collected. This is partly a function of poor networks: no single company has the capability to collect and dismantle this scrap and process the material through to refined, chemical-grade minerals fit for reuse in manufacturing.

At stake is the mining sector’s ability to plug a worrisome deficit in the metals required for the world to meet emission targets. The International Energy Agency estimates that 35 million tons of green metals will be required each year by 2050. Glencore reckons up to 40% of world demand for decarbonising metals, such as copper and nickel, can be sourced from recycling efforts such as its own. But it needs greater collaboration.

The urban mine, as Glencore describes it, is far harder to establish than a pile of twisted scrap would suggest. McKinsey & Co, a consultancy, estimates recycling will satisfy only 10% of the metals deficit by 2040.

Still, more than 80 companies and a number of organisations have been grouped by Glencore in its Circular Electronics Partnership. One consequence of Glencore’s efforts is that it may drive OEMs, including Big Tech, closer to primary suppliers such as miners. There are compelling reasons why electronics manufacturers, especially in the US and Europe, would do so. China’s dominance in specialist mineral supply is a sovereign threat to the West that it can’t ignore.

Teck

It’s no accident Nagle was hosting analysts in Canada, the domicile of Teck Corp, which Glencore is trying to buy.

Its proposed takeover has so far been met with testy opposition both from locals, with nationalist leanings, and some shareholders. According to Deutsche Bank, Glencore gets no recognition for its Canadian mines in its valuation. Buying Teck would help resolve this and, crucially, enable Glencore to hive off its thermal coal assets in a separately listed company after first merging them with Teck’s metallurgical coal mines — which would be something of a coup for its green leanings.

Following Teck’s rebuff of Glencore’s takeover proposal, Nagle returned with a smaller, but no less valuable alternative plan to merge their coal mines. Before Glencore’s approach this was something Teck had been trying to do. But even this plan stumbled after Indian firm JSW emerged as a rival bidder.

Now politics appear to have taken the narrative away from India after the killing of a Sikh independence activist on Canadian soil, allegedly by agents of India, according to Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau. “Recent political developments between India and Canada could materially change the relative completion risks of the competing bids,” said Deutsche Bank analysts in a recent report.

That’s great news for Glencore, bearing in mind roughly 30% of shareholders voted against its 2022 Climate Report in April. Ridding itself of coal while banging the drum for the circular economy are exactly the noises shareholders want to hear.

This article was first published in the Financial Mail.