[miningmx.com] – SPEAKING for the tongue-tied male half of the species,

a diamond ring delivers a certain coup de grace to a marriage proposal. Firstly, it’s

sparkly. Secondly, it’s expensive. And, thirdly, perhaps because of the second point, it

means we’re serious.

Yet the question is, how can a shiny, glass-like stone carry such resonance? What

social meme justifies the abandonment of sense, and such a reckless raid of the

annual purse?

Chemically a diamond is the twin mineral of graphite; in the popular consciousness,

however, super-heated carbon, flung from the throat of an ancient volcano equals

unfathomable, undying love.

Clearly, it’s brain-washing. Or is it that De Beers, the world’s best known producer of

diamonds, has over the decades been able to re-invent an image and give voice to

romantic love that generations of women and men only too gladly want to adopt.

To some extent, the moment that kicked De Beers’ marketing genius into action was

1947 when a young copywriter penned the lines “a diamond is forever’. In so doing,

he set down the blue print that not only formalised romance, but also created a

business model that cuts across economic and cultural boundaries.

It’s the reason, for instance, why accessing China has proved a relatively straight-

forward affair for De Beers. It just takes time, and expert marketing.

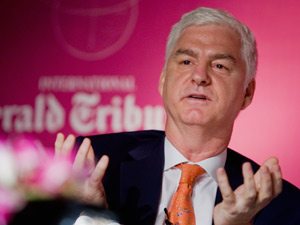

Stephen Lussier, CEO of De Beers’ unit Forevermark, was one of the first of the

diamond firm’s executives to set foot in China with business in mind.

Arriving there in 1993, he might have doubted his company’s famed market radar.

Back then, China was a society where ox-pulled carts jostled with cars.

Lussier needn’t have worried. And, in truth, he probably wasn’t. After all, De Beers

had already converted a large portion of Japanese society to accept the diamond

wedding convention, a process it began in the late Sixties.

Lussier says the rate of adoption in China, however, has been faster. “Whereas it took

half a century for half of Japan’s brides to be diamond ring holders, it has taken only

a decade to convince 55% of brides in centres where diamonds are available in

China,’ he says.

Some simple lessons from first selling diamonds in Japan were carried to China.

“Although the cultures were different, and they celebrated weddings differently, there

was still an underlying need to have symbols just the same,’ says Lussier.

“As in Japan, we focused on weddings,’ says Lussier. Weddings work for De Beers’

sales strategy because it’s a life-changing event that can support the economic

argument for a diamond. “We articulated this in a Chinese way, but the model is the

same everywhere,’ says Lussier. “It was just quicker in China.’

Today, China is a major point of growth for the De Beers’ diamond market; especially

since in established markets – such as the US and Europe – the strategy is to preserve

market share amid competition for discretionary spend that includes holidays, a car,

and other luxury goods.

In the US, De Beers wants to ensure diamonds remain the symbol of love for a new

generation of brides, while getting the older generation to be multiple diamond

owners. In some cases, De Beers targets a very specific sliver of the population:

households with an income over $175,000 (R1.6m) a year that would already own four

diamonds.

De Beers’ recent “Centre of my universe’ campaign, searchable on YouTube, is one

such effort targeting the multiple diamond owner.

A warning to cynics, however: the sentiment is applied in liberal strokes. To the

unsuspecting, however, it throws soft beams of radiance on the wife and mother to

which it attaches the question: what is the value?

Enter, the diamond: three billion years old; the hardest substance on earth; and

beautiful to boot. As in any De Beers campaign, the diamond in the shop has a price

point, but the message is priceless.

In China, the market growth potential for De Beers is vast. “In ten to 15 years, China

will represent about a quarter of the world market,’ says Phillipe Mellier, CEO of De

Beers, in an interview with Finweek. It’s that important.

Currently, De Beers sells diamonds in 30 different Chinese metros that extend well

beyond the established centres of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. “Bear in mind,

that a Tier 2 city in China probably contains about 10 million people,’ Lussier adds.

Forevermark, a water mark of ambition

What’s interesting about De Beers lately, however, is not just its focus on diamond

sales in general, but on growing its own branded line “Forevermark’. The business was

started in 2008 with Lussier becoming its CEO a year later.

Analysts have been critical. Forevermark is dismissed as a negligible part of the

overall De Beers business, and that is conflicts, cannibalises even, the joint venture

De Beers signed in 2001 with French luxury goods company, LVMH Moet Hennnessy

Louis Vuitton. This was an agreement in which De Beers has sought to build its own

fully-fledged retail presence which it called “De Beers Diamond Jewellers’. London’s

Old Bond Street shop is the flagship.

“We see it as complimentary,’ says David Prager, global head of De Beers’ corporate

affairs. “Forevermark is a brand that is right for some consumers but not for others,’

he says.

For Lussier, the aim is to make Forevermark one of the foremost luxury brands in the

world, and not just in the premium diamond market. This is a brand that is marketed

to compete with the highest value consumables out there.

That may be true, but the brand doesn’t currently register among top brands in the

luxury goods line, however.

According to a 2012 survey by Interbrand, the top luxury brand is Louis Vuitton, a

manufacturer of handbags, which has a value of $23.6bn; it is followed by Gucci –

judged the world’s 38th most valuable brand – with a value of $9.4bn.

Top 5 luxury brands

Louis Vuitton. 17th in world’s top brands (2012). Worth $23.6bn.

Gucci. 38th. $9.4bn.

Hermes. 63rd. $6.2bn.

Cartier.68th. $5.5bn.

Tiffany & Co. 70th. $5.2bn.

“Just because we are De Beers doesn’t mean we can build a brand overnight,’ says

Lussier. “Diamonds are an infrequent purchase and retailers take time to adopt

Forevermark because it is a big commitment.’

Controlling the value chain

Brand building has changed among luxury goods makers in the past ten years.

According to a report by Deutsche Bank in 2012, it was noted that luxury goods

producers were assuming greater control over the so-called value chain, the

constituents or steps in the manufacturing process that goods go through before

reaching the point of sale.

For instance, Richemont used to rely on Swatch for movement or component parts.

Sourcing its own components meant higher opex and capital costs, but it resulted in

an 11% increase in terms of return on capital expenditure over the last 10 years.

Prager acknowledges the usefulness of control over the pipeline. To an extent, De

Beers’ Forevermark does ask consumers to segment the monumental power of

diamonds with the question: why not buy this particular type of diamond? But Prager

sees departures too.

Some 10% of diamonds selected as a Forevermark diamond are not recovered from

De Beers’ mines which means the diamond company doesn’t have full control of the

chain. More importantly, the entire process of producing a Forevermark piece of

jewellery is highly collaborative.

The way it works is that De Beers selects only certain diamonds to qualify in its

Forevermark range – about 1% of total diamond trade – to which it matches only

certain cutters and polishers (manufacturers), and only certain retailers. Crucially, the

manufacturers have the freedom to produce the polished goods as they please, while

retailers have a high degree of freedom to display the Forevermark as they wish. This

makes the brand a three-way joint venture. “It is something of a hybrid,’ says Prager.

One can see why De Beers might want it this way.

The company has only been recently allowed unfettered trading in the US after

settling a long-standing anti-trust dispute with the US authorities for $295m. That’s

because for many years, De Beers controlled the diamond market withholding

unpolished supply of diamonds in order to create supply. It was price manipulation De

Beers denied for years. Even now, its officials whince at the mention of “syndicate’ in

relation to the De Beers brand.

In some respects, those were dark days for De Beers. By starving and feeding the

market, De Beers also assumed a custodianship of the market that saw it pay for

most of its advertising. Rival groups piggy-backed off its success. It also encouraged

manufacturers to join its single channel of rough (unpolished) diamond supply. By

delisting in 2000, De Beers sought to refashion itself into a more competitive

organisation.

Even as a private company, however, De Beers has not been able to avoid market

potholes. In 2009, it chopped back production, stopped paying dividends, and had to

rely on some $500m in shareholder loans ($200m from the Oppenheimer family which

owned 40% of the company then), and taking total shareholder loans to $817m. A

$1bn rights issue was required.

Notwithstanding some of the scepticism around the first few years of Forevermark,

there are signs of progress.

“We will have opened 1,000 doors within the next couple of weeks of independent

chain jewellers selling Forevermark diamonds,’ says Lussier. “We have seen a 35% to

40% annual growth over last few years, represented by diamonds inscribed’. The

table of each Forevermark diamond bears a 0.05 of a micron deep inscription,

invisible to the human eye but nonetheless intended as a compact between jeweller

and consumer of the gem’s inherent quality.

Included in this is the fact each diamond’s provenance can be verified. A decade ago,

the emergence of conflict diamonds threatened to destabilise the world’s diamond

market. Although conflict diamond trade represented only 4% of world diamond trade,

their position as symbols of lifelong love was threatened, unseated even by the

association between conflict diamonds and war, child soldiery and civil strife.

Says Lussier: “Conflict diamonds is something the industry has put a lot of effort into

addressing. Now we’ve moved beyond that. Conflict diamonds are a non-issue

compared to social responsibility. Consumers in the “Y Generation’ in Europe and

America are interested in brands that hae social responsibility attached to them’.

It is slightly curious that in a luxury business where visible consumptive power is

paramount, De Beers should be selling in Forevermark a product where the chief

quality is hidden, almost as if, in this unique case, secrecy trumps display.

In any event, the scourge of conflict diamonds seems to been kept at bay. There’s no

greater illustration of this than the fact US first lady, Michelle Obama, wore jewellery

set with Forevermark goods at Barack Obama’s second inauguration earlier this year.

Lussier is quite open about the value of marquee events and high profile personalities

in edging Forevermark higher up the brand food chain. “The power of celebrity is

especially strong. You just get a bigger bang for your buck if you succeed, and

especially among the stars in Hollywood because they are globally recognised,’ he

says.

There’s a story that confirms the extent to which De Beers will go to establish a

connection between glamour and diamond jewellery. During the Nineties De Beers’

loaned diamond jewellery to the producers of prime time show, Baywatch, which had

scripted the marriage of one of the characters. However, the loan was only made on

condition a key De Beers marketing message was embedded in the script: that a

diamond ring had only cost two months’ salary – a then necessary message for De

Beers as it sought to access a lower part of the US market – a strategy Lussier calls

“the democratisation of luxury’.

De Beers has lost none of its cunning edge. Speaking to diamond industry publication,

Rapaport Magazine in December 2011, Sally Morrison, chief marketing officer for the

US branch of the Forevermark business unit, said that each marketing campaign was

aimed first at women where the imperative was to drive desire for diamonds.

Affluent female consumers are exposed to the aesthetics of the brand long before the

holiday season which traditionally starts from the Thanksgiving period in the US

through to Christmas. Forevermark then targets the male audience. “In terms of

speaking to a male audience, it’s more about the rationale of the brand – the quality,

rarity, sourcing,’ said Morrison.

According to Lussier, Forevermark is well on its way to climbing up the luxury brand

ladder. The expectation this year is that some 200,000 diamonds will be inscribed. In

total, some $1bn of Forevermark diamonds have been sold since 2008. By way of

comparison, De Beers recorded total sales of $6.1bn in its 2012 financial year, a 16%

year-on-year decline.

“It is complimentary to unbranded diamonds,’ says Prager of the Forevermark. “But

there are those that want more out of the purchase. We don’t think we are

cannibalising diamonds as identifying a separate need and then filling that need,’ he

says.