WHETHER you are in Washington, Kinshasa, Beijing, Johannesburg or London, critical minerals are high on the agenda. It is the topic of conversation in the corridors of power, a negotiating tool in conflict-ravaged regions, a must-have in investors’ portfolios and the promise of rewards for mining companies, their shareholders and governments.

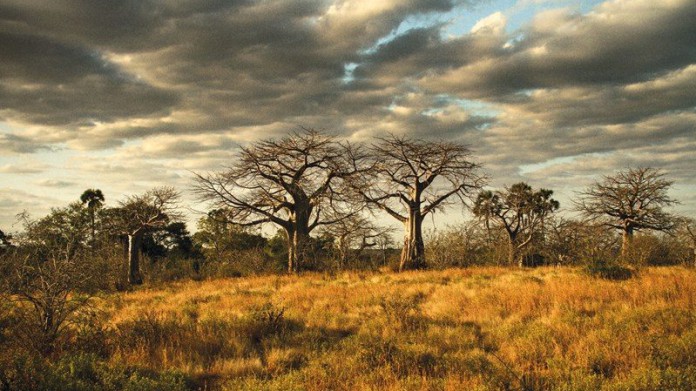

In this new rush for critical minerals, Africa with its key mineral deposits of copper, cobalt, manganese, lithium and platinum, among other minerals, is in a fantastic position to maximise these resources.

It may be trite to say that miners go where the orebodies are, but that doesn’t make it less true. Countries endowed with these riches have the opportunity to secure mining investment, and if they provide a conducive environment for industries and suppliers associated with mining to flourish, the economic benefits will be multiplied.

But in the context of competing political agendas, shifting alliances and conflicts, who wins and who loses out on these opportunities will play out in this new cold war of words, not only in politics, but in how and where to allocate capital.

African countries need to achieve a fine balancing act on the one hand, navigating the temptation of rents with the needs of mining companies and investors. There will be no easy wins. And sometimes, countries need to be both pragmatic and careful what they wish for – take for example, Botswana – which is finding that diamonds may not be forever, while Zimbabwe is quietly nurturing a few very successful platinum group metal mines.

This week, 24 – 25 June, at the London Indaba, CEOs of global mining companies, senior government officials, including Winston Chitando, Minister of Mines and Mining Development in Zimbabwe and Phumzile Mgcina, Deputy Minister of Minerals and Petroleum Resources in South Africa, and analysts and investors will discuss these issues.

The theme of this years’ London Indaba is Africa’s critical role in the minerals and metals of the future, and why the continent is important for the future of mining and mining important for the future of Africa.

The winners in this new minerals rush will be those countries and companies who are quick off the mark, pragmatic and bold. The window of opportunity may be narrow as no-one knows at what level and when the cycle will peak and how deep the dip may be. Demand for critical minerals may be driven by the drive for more weapons, as the rapid rise in European defence-related stocks are showing.

On the other hand, the appetite for these minerals may slump if the conflict between Iran and Israel engulfs other countries and economic growth in Europe, Asia and the US becomes a casualty of a wider war. Trade protectionism is already expected to dampen global economic growth.

Conflict aside, mining companies and funders seeking the returns that these essential minerals potentially offer have to carefully assess investment in regions where political instability, weak governance and infrastructure challenges make it difficult to build a business that has a long investment horizon.

African countries can attract this type of investment if they can position themselves as desirable locations for mining companies to explore or expand existing mines. This can be achieved through stable policies, laws and regulations, and by not unreasonably pursuing companies for additional tax revenue when the state coffers are looking a bit dry.

African countries also need to weigh up what benefits their trading partners, funders and mining companies bring to the table. It can never be a one way street. Everyone talks beneficiation, for example, but to get it off the ground requires the right policies and deep pockets with dollars.

And there are new players on the block – it’s not simply East versus West. The US has clearly indicated its quid pro quoapproach to securing critical minerals, Europe is emerging as an independent and responsible partner that is interested in the integrity of the value chain, while Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds have quietly intensified competition, backed by enormous financial clout. As part of assessing these competing interests, African countries need to consider the role investors will play for the long term.

Another interesting discussion we will be pursuing is whether mining companies, investors and governments will back track on ESG commitments in the face of the US administration undermining these efforts. Just think for a moment, of DEI targets becoming illegal?

My take is that major companies, even if they wanted to, would have their credibility shot if they retreated on their commitments to the work they have held up over the years as evidence of their good corporate citizenry. Abandoning the initiatives and projects to reduce emissions, conserve water, invest in host communities, advance diversity and inclusion, and strengthen governance is not a good look for a mining company or its CEO. But we will put this issue to delegates in what will no doubt be a lively debate.

As always, though, these discussions and debates need to happen.

Swanepoel, a former mining CEO and director of mining companies, is convener of the London Indaba