TWO controversies currently underway in South Africa’s mining sector have thrown into question the role played by business rescue practitioners (BRPs). It’s not the first time the efficacy of the business rescue process has been queried.

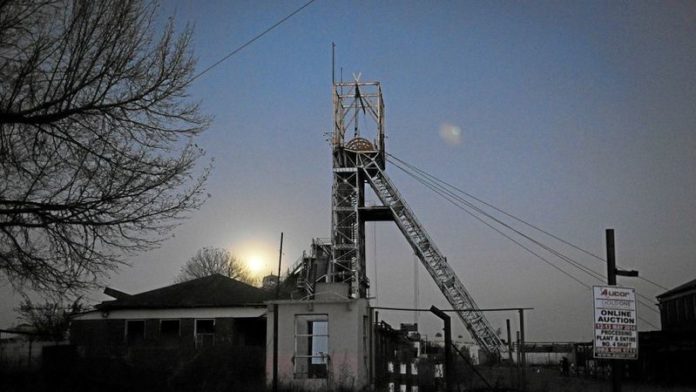

Readers may recall the whirlwind created by Enver Motala who was the BRP in the winding up of the Orkney and Grootvlei gold mines, previously owned by Pamodzi Gold before they fell into the hands of Aurora Empowerment Systems, the firm owned by Khulubuse Zuma, among others.

Motala was one of the BRPs who in 2009 accepted Aurora’s R600m bid for the Pamodzi mines only for workers’ salaries to then go unpaid. By the time Motala was removed from the process in 2011, workers still hadn’t been paid and the premises were being stripped of all tangible assets. The rest is a tragedy still playing itself out in the courts.

Mandated by the Companies Act, BRPs are called upon to save corporate entities that would ordinarily fall into provisional liquidation proceedings.

As turnaround experts, they are tasked with serving the interests of all stakeholders, but the common criticism is that it’s creditors who have the means to exert the most influence. Employees are often last in line in this process; they are frequently, if not always, the roadkill of any corporate accident.

One of the more recent controversies which has BRPs at the centre is the proposed turnaround of Optimum Coal Mines, previously owned by Tegeta Exploration and Resources, a Gupta-family company. Once again, employees of the distressed asset find themselves without pay months after the BRPs have taken control of the company.

Bernard Swanepoel, the former Harmony Gold CEO whose Last Mile Fund is participating in the Phakamani consortium bidding to take Optimum Coal Mines out of business rescue, said in an interview with Miningmx that one of the problems is the BRPs are paid by the hour and, in the case of Optimum, receive a “success fee” on asset sales.

According to Swanepoel, this double fee structure potentially conflicts the BRPs such that they might neither move quickly, nor seek the right buyer for the asset. Said another coal mining executive who asked to be anonymous: “Optimum should be a $1 deal with the funds really going into the mine”.

Asked if he was incentivised by a transaction fee, Kurt Knoop, one of the BRPs for Optimum Coal Mines, responded: “The Companies Act and Companies Regulations prescribe specific fee parameters applicable to BRPs. The fees that we charge fall within these prescribed parameters”.

Still, the sale of Optimum Coal Mines has not been a smooth process. First, an unknown company called Project Halo, which was allegedly outside the bid process, was awarded control of Optimum Coal Mines. Then the process was stopped and requests for fresh bids were asked, presumably after it became clear Project Halo may not have the upfront money it claimed it had.

The process was occluded further when the Central Energy Fund’s African Exploration & Mining Finance Company (AEMFC), stepped into the bidding process. It issued a press release with scant detail and refused to take questions. Miningmx queries to Sizwe Madondo, head of AEMFC, went unanswered.

“The AEMFC hasn’t even done a due diligence as far as I can see,” said Swanepoel. “What we’re saying – and which probably made the BRPs dislike our bid from the beginning – is that R1.2bn of the purchase price for Optimum should be spent directly on the mine first.”

In Phakamani’s offer, Optimum Coal Mines’ creditors would only be paid out of proceeds from the mines’ activities. This would make its offer less popular that Project Halo’s which largely consists of the purchase offer of which the BRPs get a cut. Phakamani has bid R2bn for Optimum Coal Mines.

The second controversy is a lesser known (but no less) acrimonious row between a black-owned company known as Siyakhula Sonke Empowerment Corporation (SSC) and the BRP of Vantage Goldfields, an Australian firm that owned the Lily gold mine where three miners tragically lost their lives following a collapse of ground in 2016.

Fred Arendse, the founder of SSC accused Rob Devereux, a BRP employed by Strategic Turnaround Solutions (Sturns), of effectively “capturing” Vantage Goldfields instead of allowing SSC to take control of the mines – a claim Devereux told Finweek was nonsense. As far as he’s concerned, Arendse hasn’t paid in SSC’s share of capital considered necessary to make R150m from the Industrial Development Corporation unconditional.

The last word goes to Lara Kahn, an attorney at Webber Wentzel, who deals regularly with BRPs. In her assessment, business rescue legislation, which dates only from 2008 and was first put into practice in 2011, is insufficiently applied owing to thin on-the-ground resources. “There’s a disconnect between the administration and the practice,” she said.

This means that of the hundreds of BRPs are many qualified, capable, committed individuals, and a fair many opportunists who may not act in the spirit of the legislation.

But the absolute clincher is that BRPs can only be removed through court proceedings. “It’s hard to get in front of a judge; we’re talking a process of months” – a reality that makes monitoring less fastidious BRPs almost impossible.