THE exploration strategy South Africa’s Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) published in April sets a bold target of attracting 5% of the world’s global exploration spend. But the industry says the department’s good intentions are not supported by a realistic plan of action. And that’s to put it mildly.

On April 14, the DMRE published South Africa’s much-anticipated exploration strategy in the Government Gazette. Industry and investors hoped the document would signal a turnabout in the country’s dwindling exploration spend (see graph: Budgeted exploration spend). In tandem with the strategy document the DMRE also published an exploration implementation plan.

Whereas the contents of the implementation plan resembled points that had been negotiated with industry, the exploration strategy appeared to be the solo work of DMRE officials.

“Hours of workshopping and negotiating with the DMRE … and what arrived on paper is not what we had expected,” says Errol Smart, head of the Minerals Council’s exploration and junior mining desk.

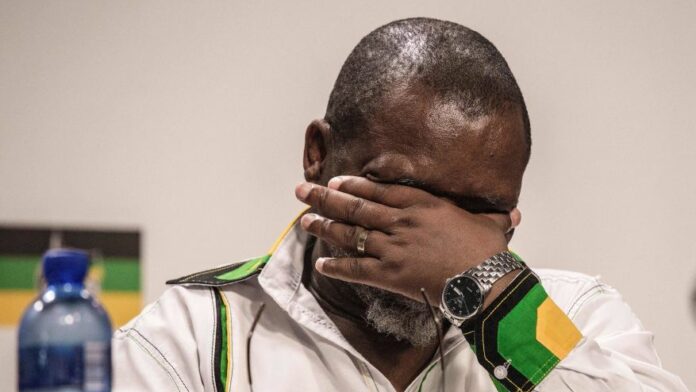

Since the publication of the two documents, mines and energy minister Gwede Mantashe has said that the exploration strategy is a draft and hinted that changes could follow after consultations with industry. But Paul Miller, a mining expert and owner of the consultancy AmaranthCX, has his doubts.

“The question is: what is the status of this document? It was gazetted, but not for public comment. At no point has it gone out for consultation, like with any green or white paper – something a normal policy process would require. The ministry has claimed widespread consultation with the industry, but that’s a lie.”

The ministry has claimed widespread consultation with the industry, but that’s a lie.

Several obvious stakeholders, such as geological and geophysical experts, were not asked to give input. “This is completely off the books from a normal policy development or regulatory or legal development process,” Miller says.

Jonathan Veeran, a mining lawyer at Webber Wentzel, says the exploration strategy is a policy document. “This is the DMRE saying ‘this is where we want things to go’, within the regulatory framework that already exists.”

An unrealistic, unfunded target

The preamble to the exploration strategy is an ambitious target of capturing 5% of the world’s global exploration spend worth about $900m, an objective Mantashe has articulated at several mining conventions. It’s a tall order though: South Africa last laid claim to this share of exploration spending in 2003. In fact, mineral exploration in South Africa has been dwindling for years and was estimated to be as little as 0,75% of global spend in 2021 (see graph on SA share of exploration spend vs Mantashe targets).

This article first appeared in The Mining Yearbook 2022 which can be accessed free of charge here >>

The ambitious target has an equally ambitious deadline: the strategy aims to attract this share of global exploration expenditure by 2025, but Miller believes the strategy and its bold deadline are dead in the water. “By the department’s own reckoning, this percentage means investment of R14bn [about $900m]. This is a radical target, requiring a radical plan. Where are the radical investments required to reach that?”

Empowerment back on the books

Much to the surprise of industry and notwithstanding Mantashe’s promises that exploration firms would be released from empowerment obligations, a 51% black ownership provision made its way back into the exploration strategy. According to the document, the DMRE will, after identifying worthy projects, only render financial and technical support if the exploration company has at least 51% black ownership.

Veeran says it’s nonsensical to have an empowerment partner at exploration stage. “At exploration level you don’t make any money. There’s no benefit created for the empowerment partner [at exploration stage].”

Moreover, exploration is a high-risk venture, and venture capitalists don’t want to part with equity given the uncertain outcomes. “Ordinarily, if you buy a house and someone says: ‘yes, you own the house but someone else has a casting share’ you’ll take a different view. This same simplistic principle could be attributed to [exploration] companies. They put in the money and should be free to manage it. They want less interference,” Veeran says.

Mining executives have long complained that regional DMRE offices still insist on proof of 51% black ownership for exploration applications, notwithstanding the fact that empowerment is no longer a requisite in the Mining Charter.

“One of my big gripes is that the minister has repeatedly said in terms of the charter you don’t require 51% BEE to get an exploration licence. Yet, the regional offices still apply it. Surely, it’s in the minister’s power to tell his regional directorate not to do it. It creates market uncertainty,” says a mining executive.

Enter the Council for Geoscience

In the strategy, the DMRE also assigns a much more prominent role to its Council for Geoscience (CGS) in the to-be-established public private partnerships. This body will be “fundamental in assessing the potential of projects that will be funded”.

Much to the relief of industry, the strategy document stops short of saying the CGS will take a stake in the ventures where it has conducted exploration work. The council’s CEO, Mosa Mabuza, suggested this as a possibility at the 2021 Junior Mining Indaba, provoking a shudder among the audience.

The council has since put these aspirations to rest. Says Mabuza: “When the CGS was founded in 1993, it was expressly prohibited from undertaking exploration. Legislation was subsequently amended, and the council was permitted to do some level of exploration participation and activities. But first and foremost, we are a science council. I want to be clear we’re not an exploration company. If we do invoke and deploy this provision [participating in exploration], we can hopefully deliver some successes. We’ve got so much potential, but the level of exploration activity is inconsistent with the quality of geology we have.”

Miller points out that the CGS will need a significant budget increase from its current annual $550m and there will have to be a significant rise in annual mineral and evaluation expenditure to be able to play a significant role in exploration. “Only half of the CGS’s current budget is spent on projects,” he says.

What we do need is a mining cadastre that will tell you exactly everything that is known about a specific site, who owns it, who has rights to it and who did work on it in the past. That’s what we need.

Some industry players are sceptical of the CGS’s significance in exploration. Says one exploration company: “If we had a transparent and efficient mining and exploration title system, industry could have saved itself. It would get offshore financing; it would bring in foreign direct investment and we would have exploration. The CGS is useful, but not defining.

“What we do need is a mining cadastre that will tell you exactly everything that is known about a specific site, who owns it, who has rights to it and who did work on it in the past. That’s what we need.”

The glaringly absent cadastre

Unsurprisingly, the strategy document also did not mention any steps to establish a new mining cadastre to replace the dysfunctional and untransparent Samrad (South African Mineral Resources Administrative System). “The big issue with Samrad is that it’s untransparent. Applicants for licences cannot tell from Samrad if a property thought to contain mineral deposits has already been claimed,” a geologist says.

“We need a cadastral system that is transparent,” says Veeran. “If I didn’t get my right, I need to see who got it and why their application was better than mine. [There seems to be an attitude of] ‘we have the resources, so we’ll dictate what happens and who gets the right. We’re the only people who can make the right decision.’ That’s a fallacy.”

The CGS’s Mabuza is hopeful that the country will have a new cadastre “sooner rather than later”. “Our minister is painfully aware of the challenge the delay is causing. It greatly affects our ability to achieve our dream. He has taken it upon himself to do all he can to make sure the system is up and running. I think he’s tired of making announcements.”

It shouldn’t be up to the minister

While the exploration strategy says the DMRE and CGS will together identify and assess projects with potential, the exploration implementation plan amplifies the role of the mining minister in the granting of exploration permits, a major concern for industry.

Roger Baxter, CEO of the Minerals Council, raised this during his address at the Junior Mining Indaba conference in Johannesburg in June.

In the plan, the DMRE says it wants to do away with the principle of ‘first come first served’ when exploration licences are granted. This principle is explicitly stated in the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act. In the exploration plan, the DMRE however laments the “unintended consequences” this principle has had, claiming it has promoted “mediocrity in the implementation of exploration activities”. The department proposes it be replaced with a meritocratic system that considers “national development imperatives”.

According to Baxter, this suggests an elevated level of ministerial discretion, which could mean exploration rights will be granted on the basis of subjective criteria by the DMRE, as opposed to a legal requirement.

This article first appeared in The Mining Yearbook 2022 which can be accessed free of charge here >>

Webber Wentzel’s Veeran says although there will always be ministerial discretion in legislation and policies, such powers cannot be unfettered. “It doesn’t mean there’s carte blanche. You can’t just leave it up to a minister to decide arbitrarily who gets an exploration right. [The qualifying criteria] must be clear and upfront from the start.”

If the first-come-first-served principle is to be replaced with a meritocratic system, the DMRE will have to change the Act, says Miller. “You can’t implement this change without a change to the law.”

According to Miller, the DMRE ignored the first-come-first-served principle for years, and granted rights to people who had no merit. “Now they want to fix their own mess by introducing some kind of meritocratic discretion. We’ve always had this principle in the Act, but they ignored it and now they want to reintroduce it. It’s entirely misdirected. It’s like fixing a broken ankle by amputating the whole leg.”

No exploration, no future

Amid the policy inertia and shortcomings in the new exploration strategy and plan, South Africa’s mining output has been shrinking. One of the biggest contributing factors is the dismal rate of discovery of new deposits (see graph: Gross fixed capital formation). Mining has been the biggest contributor to a R200bn tax windfall, and the country has vast amounts of minerals beneath the soil — a fact the DMRE boasts about in its strategy document.

“But you cannot use mining as a catalyst for growing your economy if you don’t do greenfields exploration,” says Veeran. “We seem to have an attitude in South Africa that we’re the only jurisdiction with gazillions of dollars’ worth of minerals.”

He also worries that, apart from contradicting policies that fuel uncertainty among potential investors, South Africa is also not planning to take advantage of the battery minerals revolution. This includes vanadium, cobalt and lithium, which are in high demand.

“Apart from the platinum group metals, government is not creating an environment that will drive exploration for these minerals. We need to continually have an exploration cycle. What’s going to happen when all the ores we have are mined? We’ll become one big gold mining dump.”

We don’t have time. Our minerals are being depleted. We’re already 10, 15 years behind and we have to play catch-up, but we can’t do it when the industry is in this state.

It’s simple: when mining companies don’t do greenfield operations, there aren’t new minerals lined up to be mined. It can take 20 years or longer and vast amounts of venture capital to reach production stage. Many mines in South Africa are heading towards the end of their lifespan, and new mines need to be discovered and developed if the industry is to continue.

James Lorimer, the Democratic Alliance’s spokesperson on mining, found the DMRE’s exploration strategy to be a far cry from the game-changing policy it was supposed to be. “It was supposed to signal a turnabout in the fortunes of the industry. Instead, it is a mishmash of everything government has been claiming it’s doing for the last several years.”

Taken as a whole, DMRE’s hijacking of the exploration implementation plan workshopped with the industry, and then the confusing policy assumptions in the exploration strategy, represent the kind of message that’s been putting investors off South African minerals investment for years. It accounts for the seemingly inexorable slide down the rankings of the Fraser Institute, a research company that annually gauges the attractiveness of the world’s mining regions to investors. A glance at the institute’s latest policy and investment attractiveness index shows South Africa languishing near the foot of the table, not far from Zimbabwe and flanked by the failing economies of Venezuela and Kyrgyzstan (see Fraser Institute graph).

The clock is ticking. “We don’t have time,” says Smart. “Our minerals are being depleted. We’re already 10, 15 years behind and we have to play catch-up, but we can’t do it when the industry is in this state.”

This article first appeared in The Mining Yearbook 2022 which can be accessed free of charge here >>