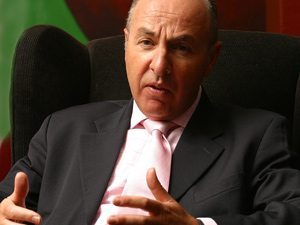

[miningmx.com] – SOMEBODY MUST HAVE put something in Peter Leon’s tea. Here he was, Webber Wentzel’s fiercely intellectual mining and energy leader, bestowing rare praise on the South African government’s 10-year regime of mining legislation.

“Let’s give credit where its due,’ said Leon when asked to reflect on what had been achieved since the promulgation of the Mineral & Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) in 2004. “It’s created a junior mining sector that didn’t exist before 2004; it has stopped mining companies sterilising reserves, which is positive, and there’s much greater black ownership of the mining industry and in employment equity’.

“The industry has been deracialised. These are all positives,’ he said, adding that he still remained critical of many other aspects of the legislative framework.

Certainly, there’s a view that without the MPRDA, the South African mining industry would have failed to respond as vigorously to the demands of the democratic era. Given the centrality of the sector to South Africa economically, this would have been lethargy of disastrous consequence.

Yet inevitably, with the finale of the mining charter around the corner, important questions are being asked as to the cost of the South African government’s efforts to engineer social and economic change by writ.

As crucially, there is worry about the government’s intention to shape future legislation as it seeks to address the failures of the MPRDA and the mining charter. Amendments to the MPRDA, that were due to be signed into law, have returned South Africa’s mining sector to a new period of uncertainty.

Amendments to separate legislation supported by government’s Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), known as Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBB-EE) Amendment Act, has provided different guidelines from those in the mining sector. This has led to questions as to whether the MPRDA and the mining charter can be superceded by the BBB-EE.

COMPROMISE

The mining charter in its current form was a compromise document after it became clear that the South African government’s first position on empowerment was akin to nationalisation.

Widespread liquidations of mining shares in the week that followed the leak of the government’s draft charter in 2002 demonstrated that the government could only sensibly act in dialogue if it wanted to make the sector demographically representative.

The compromise version of the mining charter set down a requirement for the mining sector to sell 26% of their shares – or units of production – to black mining firms.

This compared to government’s initial demand for 50% plus one share and was a level of ownership that, at the time, was felt was appropriate as it protected all minority interests within a company.

It was also set down that the ownership target had to be achieved in ten years (2014) with a half-term review written into the charter (2008) at which point the mining sector and government could reflect on progress to date, and make recommendations for the future.

The charter prescribed a number of additional requirements besides the 26% equity target, including demands for procurement of services by black-owned companies, employment equity targets, and improved labour and social plans.

Yet it was the 26% ownership target that captured the headlines. Certainly, it transfixed the attention of companies and became the most important yardstick by which success or failure in the empowerment stakes was measured.

“On the equity side, the mining charter was about building a black middle class, and less about value creation,’ said Andrew Mitchell, a partner at Fasken Martineau. The result was that communities around the mines were effectively excluded from the empowerment equation.

“In the first wave of black economic empowerment (BEE), companies chose the businessman and said this was BEE,’ he said. The momentous social upheavel around the platinum mines at Marikana in South Africa’s North-West province town of Rustenburg is now interpreted as a consequence of this oversight.

An additional problem was that the design of corporate transactions structured to achieve 26% empowerment was problematic. Under-capitalised black-owned companies were almost always vendor-financed, and reliant on dividend flow to repay interest on debt and debt capital itself.

As a result, many empowerment deals failed as the commodity market turned and cash flows available for dividend payments diminished.

Questions about the capacity of the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) to administrate the empowerment laws was also questioned, and with reason. In fact, one of the important (and overlooked) amendments to the MPRDA is to debottleneck the mining licence application process to 300 days from three years.

In retrospect, the unquestionably urgent need for change in the South African mining sector was bungled, rushed even.

“Ten years down the line, the legislation has not done much for rural communities, and there’s an element of mistrust,’ said Nicola Jackson, a partner at Fasken Martineau. “Empowerment is a five-day match, and we’re trying to do it in a day.’

DAY OF RECKONING

Ten years on and now the South African mining sector faces its Waterloo. The DMR has retained Moloto Solutions, an empowerment auditing firm, to assess the readiness of mining companies to pass the mining charter test by early 2015.

Former mines minister Susan Shabangu said in February that the signs were good. “We are doing well in terms of moving towards compliance,’ Shabangu said.

This was a far, conciliatory cry from Shabangu’s comments at the half-way point in 2009, when empowerment among South Africa’s mining sector was estimated by government to be a disappointing 8.9%, below the 15% that was hoped for at the time.

South African mining companies are today mixed on how the audit will progress. Anglo American and AngloGold Ashanti have commented both publicly and privately that the process has been smooth. Neal Froneman, CEO of Sibanye Gold, is sceptical, however.

“No doubt the government will go out of its way to show how little we comply [with empowerment legislation],’ said Froneman in February in response to a question at a company presentation regarding the firm’s empowerment credentials.

One of the concerns is whether there’s willingness in South African government circles to accept past empowerment deals, the so-called “once empowered, always empowered principle’. Attorneys consulted by the Mining Yearbook said the once-empowered, always-empowered principle was never actually enshrined – a view that was supported this week when mines minister, Ngoako Ramatlhodi, said ahead of his budget speech that the principle would not be recognised.

“I don’t subscribe to that [once-empowered, always-empowered] because it defeats the spirit of transformation. There are people who are historically excluded and these people happen to be a majority. They should have a say in what happens to their minerals,’ he was quoted by Bloomberg News to have said.

Said one attorney: “Jactino Rocha [former deputy-director of the Minerals and Energy Department] drew a red line through that proposal when the mining charter was being written. He wasn’t standing for that.’

The government’s standpoint has been subsequently supported in its insistence that Northam Platinum and Aquarius Platinum address empowerment shareholdings after their respective partners liquidated shares to repay interest on loans they had taken out.

There’s also no lock-in for empowerment partners which means that mining companies post 2015 may find themselves without demonstrable BEE. It’s interesting that while the DTI’s BBB-EE legislation offers many challenges to the mining sector’s legislation, it’s view on protecting past empowerment deals is actually quite helpful.

The DTI’s BBB-EE “generic’ Codes of Good Practice acknowledges past empowerment deals (subject to certain conditions being met) for measuring a firm’s BBB-EE rating capped up to 40% of the firm’s total BBB-EE ownership score, said Pieter Steyn, a director at Werksmans Attorneys. The “generic’ Codes set a BBB-EE ownership target of 25% plus one vote.

Furthermore, whereas the MPRDA enshrines 26% BEE ownership as a stipulation before a new order mining licence can be awarded, the “generic’ codes only set out a methodology for calculating BBB-EE status on a sliding scale.

“If a company meets the full target, it will receive all the available BBB-EE points; but if you don’t meet the target, it will get a lower number of points. The achievement of targets is not binding although the amendments to the Codes (coming into effect on 1 May 2015) for the first time introduce an automatic downgrade of a firm’s BBBB-EE status by one level if certain ownership, skills development and enterprise and supplier development targets are not met,’ said Steyn.

Steyn said the DMR’s policy is often to require 50% or 51% empowerment shareholding for a licence to be issued and that the 26% is merely a minimum stepping stone to this end. The major question, however, is whether (given the fact that the Mining Charter targets are for 2014) the DMR will introduce new targets for the post 2014 period or, whether the DTI’s amended “generic’ codes will apply to the mining sector?

Webber Wentzel’s Leon referred to it as the “trumping rule’ – where there’s an instance of a company that could fall under the ambit of either piece of legislation.

In the coal sector, for instance, Eskom has asked for new suppliers of coal to it to conform to the 50% plus one share rule because Eskom reports to the Department of Public Enterprises which has adopted the DTI’s legislation.

Leon said a recent meeting between the CEO of a coal mining company with Eskom ended in aggressive terms. “They expected his company to be 50.1% black-owned in order to meet Eskom’s requirements which, of course, is nonsense,’ said Leon.

“It shows you how far this has gone and the thinking in state-owned enterprises. It points to a broader issue of the impact of amendments to BEE codes. The trumping provision is that the mining charter has to yield to what the DTI prescribes.’

Said Steyn: “The amendment to BBB-EE Act is that if a company is covered by a sector code, then the sector code applies to measure the firm’s BBB-EE status [as the governing legislation].

“But the mining charter is issued in terms of the MPRDA by the Minister of Mines and is strictly speaking not a sector code’. In fact, said Leon, the MPRDA amendment bill specifically stated that the mining charter is part of the act, providing it with additional force.

There seems to be no definitive rule.

Fasken Martineau’s Mitchell believed that mining licences were granted based on 26% empowerment targets, among other requirements, and that only a failure to meet those directives can lead to a company losing its mining right which means that even if a mining company doesn’t comply with BBB-EE, it cannot be stripped of its right to mine. It still complies in terms of the country’s mining law.

Shabangu acknowledged the exact nature of the interplay between the empowerment laws promulgated by the DTI and the DMR’s mining charter were uncertain.

Speaking in February at the Mining Indaba, Shabangu said there was “… a need to find harmonisation’.

“We don’t agree with the DTI, but we are working with them [the DTI] in discussing the two acts and in ways to find harmony,’ she said. “We don’t want to make unintended reversals on gains made in the mining industry,’ she added.

THE WATERFALL EFFECT

It would appear, therefore, that mining legislation remains a work in progress as it ever was. Again, Shabangu captures the government mood: “2014 does not end transformation. Nothing can be further from the truth. It remains a journey for all of us,’ she said in February.

According to Kevin Cron, an attorney at Norton Rose Fulbright, there’s an economic imperative for mining companies who have met 2014 targets to maintain their empowerment loadings (if not an ethical one).

He believed it made for good business sense to have a strong empowerment rating as per the DTI codes if only because it helps establish that company as a partner of choice, a state of affairs he describes as “a waterfall effect’.

“There is no official penalty for not meeting DTI codes; but the codes are economic in that if companies don’t achieve the appropriate ranking other people in other companies will not want to deal with you owing to waterfall effect.

“You would want to procure, for instance, from properly rated entity. Although the DTI’s codes are voluntary, there are practical penalties if you don’t play the game.’

This seems to be the thinking on the ground.

Speaking at the group’s March quarter presentation, Graham Briggs, CEO of Harmony Gold said his firm intended to continue building its empowerment credentials.

“Although the target is 26%, we exceed that. Where we have opportunity to do deals in our BEE structure, we will continue to do so because it’s the right thing to do,’ he said.

There’s other financial issues raised by not meeting BEE laws. “Lending is a problem,’ said Cron. “What do the lenders do if they believe a company only has 15% empowerment?’

By the same token, Cron said that the South African government has to draw a line in the sand somewhere regarding the once-empowered, always-empowered conundrum.

“It will have to be addressed or it will create funding problems, especially from non-South African institutions. What we would like to see is that if a company meets its targets in 2014 it will have been deemed to have met all its BEE targets.

“However, if the company has to apply for a new property extension, then it will have to reach new empowerment targets,’ he said.

The view from the mining sector itself is that there may be grounds for combining the DTI’s BBB-EE legislation and the MPRDA. Vusi Mabena, senior executive, transformation and stakeholder relations at the Chamber of Mines of South Africa, said this might be a possibility for the sector after the mining charter compliance has been completed in early 2015.

But he believed that more credit should be provided for previous empowerment deals. “Why should companies be penalised for creating entrepeneurs who have cashed out of the industry? Perhaps this is where other codes become important,’ he said.